Full research report

Research Team:

Christian Mogensen, Denmark

María Rún Bjarnadóttir & Þórdís Elva Þorvaldsdóttir, Iceland

Moa Bladini & Wanna Svedberg Andersson, Sweden

Click here to watch

Click here to

Index

A Joint Nordic Effort and Game Changer

Available and structured data from national courts

Social Education - Comprehensive Sexual Education

Supplementary Danish perspectives

Gendered Violence and Harassment is Not Taken Seriously

Data collected: Victim Reports

Discussion About the Victim Reported Data

Discussion About Judicial Analysis

Judicial Analysis: Data & Methods

Hovrätten för Skåne och Blekinge

Addendum 1: Icelandic Police Data on Threats

A Gendered Attack is a Democratic Attack

- Preface -

Women and minorities are disproportionately targeted, victimized and scrutinized by

most, if not all, forms of online harassment. This includes targeted sexual crimes

committed via digital means and tools, digital stalking, written threats via online media,

image-sharing without consent, doxxing, gendered slurs and more. As our worlds and

everyday lives have grown increasingly digital over the last years, so has the amount of

gendered attacks gone digital. This has led to malplaced jubilee that some problems have

disappeared (they have not), that initial policies have worked (no discernible effect) or

that the foundational gender-based differences in socioeconomic and cultural perceived

qualities have been solved (still very much there). Although the issues have moved from

the physical space to the digital, they have not lessened in severity or seriousness. As

much of our democratic, social and political discourse today takes place online, any

targeted abuse or attacks set here will also undermine all of these arenas.

As women are targeted more than men in the above mentioned cases, there is also a very

real risk that they abstain from participating in digital spaces - social, political or other

settings online provide little to no respite from the attacks. Therefore, as women exit the

online arenas, they also exit the primary settings for political/cultural/social influence,

that followingly are left with a biased and thus undemocratic confluence of participants

and decision makers.

A gendered attack is a democratic attack.

The UN recognizes gender-based violence as a serious threat to the democratic societal

fundament: “violence against women is an obstacle to the achievement of equality,

development and peace”1 and states are obliged to prevent it, both under UN and EU

laws. 2 The present research will exemplify these disproportionalities and their effect by focusing

on several separate forms of gender-based digital attacks: Sexual abuse via image-based

attacks, threats to one’s life or wellbeing, and sexual harassment (including unsolicited

genital imagery). It is of note to the research though, that the analyzed Nordic countries

all treat the three categories as illegal, but that national differences in definition, penal

code and potential punishment vary.

The research aims to both outline the severity and consequences of the abuse, but

furthermore to also provide a cursory profile of both victims and perpetrators to further

assist Nordic governments in mitigating and countering any continuation hereof.

A Joint Nordic Effort

The present analysis is a comparative research between three Nordic countries: Iceland, Denmark and Sweden. The Icelandic chapter is led by dr. María Rún Bjarnadóttir as lead researcher and Þórdís Elva Þorvaldsdóttir as researcher. The Swedish part of the research is led by Dr. Moa Bladini with Wanna Svedberg Andersson as researcher and Christian Mogensen leads the Danish part of the research. The research partnership is constituted by NORDREF and relies on a wide range of organizations with collection of, and access to, data. The project is funded by NIKK and the authors would like to acknowledge this vital contribution to the work.

By the time that this research report is published, work has already begun on creating tools and preventative materials based on the results. The research revealed that young men under the age of 25 are overrepresented among perpetrators of gender-based online abuse, particularly that which is sexualised in nature. This led to the creation of the Game Changer, an international collaboration with partners in Sweden, Finland and Iceland, including the E-sports Federation of Iceland (RÍSÍ), the Swedish gaming organisation SVEROK, the award-winning Finnish youth work Sua Varten Somessa, as well as the Violence Prevention School of Iceland (Ofsi).

The Game Changer aims to create evidence-based tools, campaigns and initiatives to counter abuse in online spaces, aimed at youth with a special focus on reaching young men using the fun methods of gaming and digital youth work. The overall aim of the project is to strengthen young people's digital rights and cyber citizenship.

The Game Changer will also envision young people's "online utopia" by gathering information about the changes to digital environments that young people deem necessary for them to reach their highest potential - and help them craft it, using methods of gaming, community-building and social entrepreneurship. This project is funded by the Erasmus+ program.

NORDREF

The Nordic Digital Right and Equality Foundation was founded in the unprecedented year of 2020, when the Covid19 pandemic underlined how important the internet is to our economies as well as our social lives - and also how crucial it is that everyone is safe to work, play and express themselves online. Safeguarding those rights is challenging for many reasons. When it comes to digital violations, online jurisdiction can be unclear. In other cases, it's unclear if legal responsibility is with users, hosts or platforms. Law enforcement is often lacking in technical know-how, and offenders can be hard to trace. Last but not least, ignorance about digital rights can make it hard for victims to determine when they've been targeted, and in some cases even for perpetrators to know when they've crossed the line between protected speech and hate speech, to name an example. A multi-disciplinary approach is needed to ensure that the internet lives up to its potential as the breeding ground for democracy, diversity and global dialogue.

Methodology

When developing the methodology for this project, the authors discussed a qualitative methodology like interviews with perpetrators as Hall and Hearn discuss in connection to the limits of their research method. They suggest that „one-to-one interviews would allow perpetrators (largely men) time and space to account for their actions in detail and victims (largely women) to record their experiences in confidence“.3 Hall and Hearn also raise that a contextualized study of perpetrators would contribute to a more nuanced understanding of perpetrators and their motives. As„ […] we know little about how this phenomenon differs for age, culture, ethnic and socio-economic groups, including homosociality, so a study of these likely variations would be recommended.“4

In light of the ethical and practical concerns involved with vying for interviews with perpetrators, the methodology builds on a mixed approach of qualitative and quantitative methods that combined shed a multi-layered light on perpetrators.

The research group ended up in a three dimensional-model of data collection, with three types of dataset in each country: one from victim/survivors from women’s shelters; one from police reports and one from court verdict.

Perpetrators of gender-based online abuse, specifically image-based sexual abuse, threats and sexual harassment, were mapped with regard to age, gender, relationship to the victim and motive, using three sources of information in all participating countries:

1. Victims: The shelters we partnered with in Iceland, Sweden and Denmark collected quantitative data from their clients using a questionnaire developed for the purposes of this research.

2. Official records: Police data and court verdicts in cases of image-based sexual abuse, sexual harassment and unlawful threats were gathered and analysed.

3. Perpetrators: Data sets and information collected in The Angry Internet, contributed by our partner Christian Mogensen, will complement data findings.

The Swedish part has gone through a research ethical assessment by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority, and is approved, see Dnr 2021-06211-01.

Theoretical Framework

The concept of the continuum of sexual violence paves way to address online

gender-based violence as violence against women.5 The concept of female fear, a fear of being exposed to sexual violence, is relevant in this context. This fear is shared by women despite their age, time and space. Women share cultural experiences and memories of sexual violence.6

This fear affects how women live their lives and limits their social and democratic engagement, as Elizabeth Stanko describes it: ”A silent oppression, an unspoken expectation of being a woman”7.

Research shows that this fear that restricts women’s lives also follows them into digital space.8

Gender based online violence mirrors and reproduces the unequal life conditions (the gender order) also in digital space.

The female fear is, argues Wendt Höjer, in itself structuring and sets limits for women’s lives. This understanding of violence against women draws on Liz Kelly’s work on the continuum of sexual violence.9 Research shows how the fear that accompanies women and restricts their lives in physical space also accompanies and delimits women’s lives in digital spaces.10

Image-based sexual abuse is a gendered harm, with many victim-survivors experiencing devastating harms because of the social and political context of the sexual double standard and online abuse of women.11 McGlynn and Rackley explain that complacency towards image-based sexual abuse can have detrimental effects on social attitudes and lead to a culture that accepts image-based sexual abuse and diminishes the consequences it can have on an individual basis. They consider this effect to appear, among other

things, in the contexts of the normalization of sexual violence, and undermining of the

notion of consent in sexual relations.12

Victims of online sexual abuse, whether it be image-based sexual abuse or other forms of sexual privacy violations, are withdrawing from the online sphere.13 Even though this retreat is symptomatic of harm on a personal level, the implications stretch further. McGlynn and Rackley warn that a lack of response to image-based sexual abuse might contribute to a culture and norms that can have a negative, long-term impact on women's participation in the online sphere.14 This can constitute a societal harm in itself, in particular, in the context of democratic discourse that increasingly takes place online.15

Furthermore as argued by Manne, the long–term implications of the sharing imagery on the internet are yet to come into light. As she suggests, this may lead to a shift in norms that will be more accepting of female nudity. Nevertheless, Manne also warns that history would suggest that less progressive attitudes will continue because misogyny and gender based discrimination persist within social structures. (Manne, 2018).

Communications with CSO

The authors were mindful of the fact that the shelters who gathered the data for this research have enough on their plate as it is. As a rule, shelters are underfunded and understaffed compared to the scope and prevalence of gender-based violence. Also, it is arguably more pressing for a shelter worker to cater to a battered woman’s immediate physical, emotional and mental needs than to present her with a questionnaire about online abuse. As a result, utmost care was taken to address all concerns and questions

that the shelter staff had, and to ensure that the data collection for this research added as little as possible to the load already carried by the shelters. This was done by figuring out how to best incorporate the data collection into the day-to-day routines of the staff. In the shelters where a comfortable method was developed around how to present the questionnaire to clients – such as in Stígamót where each client was handed a tablet and gently encouraged to fill in the questionnaire as they waited for their counselor – far

more answers were collected.

In Sweden, 256 emails were exchanged with ROKS regarding the research, ROKS’ role in the data collection and how to best incorporate the questionnaire into the daily activities of shelter staff. This volume of emails is explained in part by the fact that ROKS is a large organization with long pipelines. Moreover, the role of contact person was repeatedly passed around, which meant that the situation had to be explained all over again to a new manager a number of times. A total of 27 zoom meetings were conducted with shelter coordinators. Nine shelters were offered a free workshop about online abuse in the context of gender-based violence, in the hope that it would inspire shelter staff and help them to remember the questionnaire in their daily work. Only two shelters accepted this offer. Three free tablet computers were offered to the Swedish shelters to stimulate the collection of answers. Despite various efforts and repeated attempts to figure out the best way to make the collaboration work for both parties, the total amount of answers collected electronically in Sweden was 3. An additional 9 questionnaires were collected on paper format. The questionnaire was also translated into Farsi upon ROKS request. Zero answers in Farsi were collected. In conclusion, the choice of collecting answers from women’s shelters was more complicated than we expected. Due to the situation for the women’s shelter we are thankful for the efforts made and the answers we got, although we might not be able to make any general conclusions from the data collected.

Bjarkarhlíð Family Justice Center, Reykjavík, Iceland

In Iceland, 225 emails were exchanged with Stígamót, Bjarkarhlíð and Kvennaathvarfið shelters regarding their role in the data collection and how to best incorporate the questionnaire into the daily activities of shelter staff. Six in-person meetings were conducted with shelter managers as well as 10-15 phone calls. All three shelters were offered a free workshop about online abuse in the context of gender-based violence. All three shelters accepted this offer. Four free tablet computers were offered to two out of three shelters, when five months remained of the data collection period, and they both accepted (the third shelter already had computers in their waiting room). After the tablets were incorporated into the working method, the number of answers dramatically increased, most notably at Stígamót counseling center. The total amount of answers collected electronically in Iceland was 262.

In Denmark, 102 emails were exchanged with Dansk Kvindesamfunds Krisecentre regarding their role in the data collection and how to best incorporate the questionnaire into the daily activities of shelter staff. A total of 5 zoom meetings were conducted with shelter coordinators.The shelter was offered a free workshop about online abuse in the context of gender-based violence. The offer was accepted, but a time that suited both parties could not be settled upon. A free tablet computer was offered to the Danish shelters when four months remained of the data collection period, to stimulate the collection of answers. No more answers were submitted after the delivery of the tablet. The total amount of answers collected electronically in Denmark was 31.

The questionnaire was also translated into English and the link sent to all shelter partners in all three countries. The total amount of answers collected in English was 2. Due to the COVID19 pandemic, particularly the surge related to the Omicron variant, the data collection that was supposed to start on January 1st 2022 started at the end of the month instead. To make up for it, the data collection was extended through January 2023 instead, ensuring a 12 month collection period as planned.

Covid19

One of the negative social implications of the digitisation of communication and social interactions during the Covid-19 pandemic of 2020-2022 was a rise in digital manifestations of violence against women, referred to as the ‘shadow pandemic’ by the UN16. Digital forms of gender-based abuse and violence did however not start with the Covid pandemic, even if the pandemic exacerbated this form of abuse.Online forms of gender-based violence against women not only have a negative impact on women's personal and public lives, but have been found to have wider social and societal harms 17. Thus, curbing online GBV is important in the context of both individual rights and preserving democratic foundations 18.

The research focuses specifically on three forms of digital gendered abuse; image-based

sexual abuse, illegal threats and sexual harassment (including so-called dickpics). The aim of the research is to contribute to building a profile of perpetrators of online forms of gender-based violence and mapping out a picture of their motivation and their modus operandi. This is done in a bid to underpin evidence-based methods to curb the behavior through targeted prevention and/or deterrence action. This in turn should both have an impact on an individual rights level, as well as strengthening democracy and gender-equality.

By posing the same research question in three Nordic countries, the authors seek to

expose potential regional differences and similarities in the profile of the perpetrator of

online gendered abuse, illustrating to what extent there may be traits or motivations that

transcend borders and national perspectives. The modes of response developed on the

basis of the research could thus contribute to a regional, or even international solution to

end online GBV.

Conclusions and findings

Across all three Nordic countries, both data, viral cases and troublesome bureaucracy

bear witness to that gendered attacks are not only prevalent, but also rooted in societal

schisms, archaic legislation and a combination of disbelief and mistrust in the systems

supposed to protect victims. All three countries exhibit a propensity to allow the

weaponization of female sexuality and identity, insofar that the data readily shows that

women are disproportionately targeted and victimized by gendered and sexualized abuse

and digital attacks.

There can be no doubt that gendered attacks are both a social and democratic issue. Nor

can it be denied that these attacks are prevalent in the Nordic countries. Yet, the data

gathering collection and cooperation with local and national police, courts and CSO have

been suffering under several societal and organizational deficits. It has been evident that

gendered violence - particularly digital gendered violence - is too underfunded of a field

to satisfactorily collect and store data, in order to support research or activism promoting

any policies or projects combating the issue.

The researchers are in agreement that when issues that challenge the egalitarian

foundation of democracy are outsourced to passionate freelancers, overworked academics

and understaffed CSOs, said foundation is in dire straits. As will be argued in detail in the

following national chapters, gaining access to the data for analysis can be, as one

researcher put it, ‘like squeezing blood from a stone’. Furthermore, we acknowledge that

solving these challenges to our democratic foundations are not done overnight - they will

require either a substantial social education, or an extremely ambitious rework of

legislative praxis and police efforts (both requiring funding and re-education). This does

entail though, that the bare access to data possibly illuminating the problems, must not be

hid behind arduous bureaucracy or unwillingness to even discuss the potentiality of the

problems existing.

Data must be made available - even when it shows things we do not wish to see.

Actions and

recommendations

Available and structured data from national courts

Sorting and segmenting court verdicts with respect to digital or physical abuse,

transgressions and harassment has been an extremely taxing endeavor both for the

researchers, but furthermore also for the clerks, police officers and representatives of the

respective countries and regions. It is a paramount recommendation, to qualify and ease

any further work in this important field, that countries begin separating violations as to

the medium in which they are committed. As the method of a crime both lends itself to

understanding it, preventing it and communicating about it, it must be of utmost

importance to any political system wishing to stem these digital gendered attacks, to

clearly and readily make available how many happen, and how they were carried out. This

could be achieved with either separate penal codes, internal codes and systematization, or

any such bureaucratic update, which would allow a currently anachronistic judicial system

to understand and analyze modern crime.

Social education. Comprehensive sexual eduation.

We recognize the critical role that social education plays in combating gender violence,

particularly in the context of Nordic countries. These nations, known for their

progressive social policies, have been at the forefront of integrating comprehensive sexual

education and gender equality into their education systems. The approach taken by the

Nordic countries offers valuable insights into how social education can be effectively

utilized to combat gender violence.

Firstly, comprehensive sexual education in Nordic countries goes beyond the basics of

human biology and contraception. It encompasses a wide range of topics including

consent, healthy relationships, gender identity, and sexual orientation. This holistic

approach ensures that from a young age, individuals are equipped with the knowledge

and understanding necessary to navigate relationships respectfully and safely. By

normalizing conversations about consent and respect in sexual contexts, these education

programs lay the foundation for preventing gender-based violence.

Additionally, Nordic education systems place a strong emphasis on gender equality and

challenge traditional gender norms and stereotypes. This is crucial because gender-based

violence often stems from deeply ingrained societal norms that dictate power dynamics

and roles. By educating children and young adults about gender equality, and actively

working to dismantle harmful stereotypes, these societies foster an environment where

respect and equality are the norm.

Moreover, Nordic countries have been successful in integrating these educational themes

not just in the curriculum but also in the overall school environment. Schools are seen as

key arenas for promoting gender equality and preventing violence. This involves training

teachers and school staff to recognize and address gender-based bullying and harassment,

creating safe spaces for students to discuss these issues, and implementing school-wide

policies that reflect these values.

The involvement of the wider community is also a key component. Nordic countries

often involve parents and community leaders in educational programs, ensuring that the

messages of respect, equality, and non-violence extend beyond the classroom. This

community-wide approach helps to reinforce the values taught in schools and contributes

to a broader cultural shift.

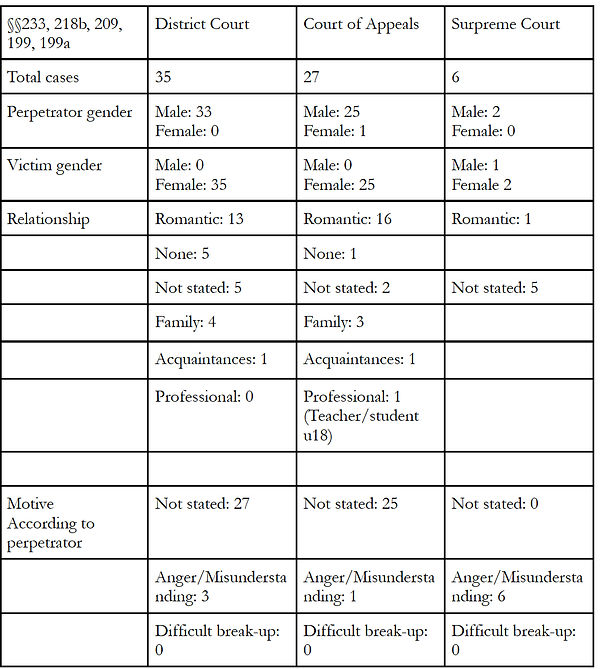

The Icelandic court data showed that an overwhelming majority of men who digitally

abused women were doing so, in order to retaliate against an ex-lover, partner or spouse,

who had ended a relationship with them, or at least a perceived relationship. This point is

also evident in the Danish data.

Finally, the impact of this comprehensive approach to social education in the Nordic

countries is evidenced by their generally low levels of gender violence and high levels of

gender equality. While no society is free from gender violence, the Nordic model

demonstrates how education can be a powerful tool in preventing such violence. By

instilling values of equality, respect, and consent from a young age and involving the

entire community in these efforts, significant strides can be made in combating gender

violence.

In conclusion, the Nordic approach to social education, with its emphasis on

comprehensive sexual education and gender equality, offers a compelling framework for

combating gender violence. This model highlights the importance of early education,

community involvement, and the challenging of traditional norms as key strategies in

creating safer, more equitable societies. As the framework exists across the countries, it

must be understood as too important to negligible one-off lessons in schools, or

something outsourced to civil society organizations. As a fundamental part of the Nordic

democratic identity and egalitarian ideology, it must be prioritized - and funded

comparatively.

Furthermore, a strong social effort in resolving some of the gendered biases could

empower more victims to report gendered crimes, for more men to understand the

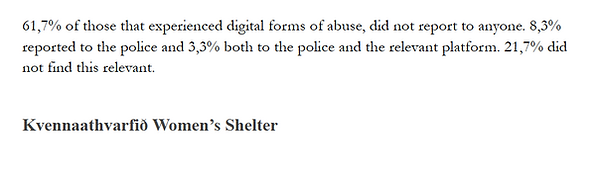

severity of them, and for the process to be less traumatic. In Iceland in particular, the

conviction rate of online abuse is noteworthy. In all cases examined, there was a full or

partial conviction. Yet still, the Icelandic data also shows that very few victims (which is

also the case in Denmark and Sweden), report such crimes to the police in the first place,

because of social biases and negative expectations about the process.

Victim Blaming

A common testimony across both Denmark, Iceland and Sweden is that victims of

gendered crimes feel a need to “convince” others of the fact that they have been the

victim of a crime. Several have said that particularly as one must report crimes as soon as

possible after they have been committed, one is in an emotionally vulnerable state when

doing so. This, in combination with the gendered perspective of herein analyzed victims

predominantly being women - women subjected to crimes by and because of their

gender, and police officers (to whom one reports crimes) historically are predominantly

men, they too often do not feel they are believed, or that their crime is taken seriously,

when reporting it. This leads to some “giving up” in the process, or even not wanting to

report the crime in the first place.

They feel that they have done wrong by being in a position in which they have been targeted.

They feel as if they are blamed for being victims.

Victim blaming in the context of gender violence is a complex and deeply ingrained issue

that manifests in various forms and settings. It refers to the tendency to question, blame,

or assign responsibility to victims of violence, rather than focusing on the perpetrator's

actions. This phenomenon is not just a social or cultural issue but also intersects with

legal, psychological, and institutional dimensions.

At its core, victim blaming is rooted in societal norms and stereotypes about gender,

sexuality, and power dynamics. These stereotypes often dictate how victims of violence,

particularly women and marginalized groups, are perceived and treated. For example,

questions about a victim's behavior, clothing, or past sexual history are frequently used to

rationalize or diminish the severity of the perpetrator's actions. This not only exacerbates

the trauma experienced by the victim but also perpetuates a culture of silence and stigma

around gender violence.

Combating victim blaming requires a multi-faceted approach. Education and awareness

are fundamental in challenging and changing societal attitudes. This involves re-educating

society to understand that the responsibility for violence lies solely with the perpetrator,

not the victim. Comprehensive education programs, starting from a young age, can play a

significant role in reshaping perceptions and attitudes towards gender violence.

The media also plays a crucial role in shaping public perception. Responsible reporting

that avoids sensationalism and respects the dignity of victims can help in altering

entrenched attitudes. Similarly, the portrayal of gender violence in entertainment and

media should be handled with sensitivity and awareness, avoiding the perpetuation of

harmful stereotypes.

Legal and institutional reforms are equally vital. The criminal justice system often mirrors

societal biases, leading to secondary victimization of survivors during legal proceedings.

Reforming laws and procedures to be more victim-centric, ensuring sensitivity training

for law enforcement and legal professionals, and providing adequate support services for

survivors are essential steps.

Lastly, empowering victims and survivors through support networks, counseling, and

advocacy is crucial. Creating safe spaces for survivors to share their stories and seek help

can significantly reduce the stigma and isolation they face. Moreover, involving survivors

in policy-making and awareness campaigns can lend a powerful and authentic voice to the

fight against victim blaming, add valuable insights and mitigate the internalization of

survivors. -It is important to note that victim blaming can be both external (done by

society onto the victims), and in some cases internalized by the victims themselves (which

will be described further followingly). Both factors will keep victims from seeking justice,

and or speaking up after abuse.

In conclusion, victim blaming in gender violence is a deep-seated issue that demands

comprehensive societal, legal, and institutional change. By shifting attitudes, reforming

systems, and empowering survivors, we can create a more just and compassionate society

where victims are supported and believed, and violence is unequivocally condemned.

The

Do's & Don'ts Conundrum

In addition to the above-mentioned paradox of victim blaming creating more victims, the

researchers would like to include a personal anecdote, that is shared across the group, and

corroborated with several colleagues, friends, family and in national narratives:

"Women are brought up with a long list of "don'ts": Don't walk alone in the dark, don't leave your drink unattended, don't send nudes, don't feed the troll, don't wear a short

skirt, don't accept friend requests from strangers, etc. When disaster strikes and the woman is targeted by a perpetrator, this further cements the notion of self-blame with many victims, who feel that after a lifetime of being trained to avoid becoming a victim of male violence, they still failed."

Further listing, promoting and teaching any such “don’s” will only extend the chokehold

this good-natured but failed approach to gender-bias upbringing has on gender-based

violence.

Comparatively, men are brought up as ‘do’ers’. Do excel, do challenge, do fight for, do be

the best, do get the prize etc. This glorification of ‘if failing try harder and do more’, risks

leading to the man facing a rejection (perceived or actual). ‘Trying harder’ in this instance

can come glaringly close to abuse or even violence, and the perceived fear of ‘falling

masculinity’ will force the man to strengthen his efforts to winning the prize - the

woman.

Ultimately this well-meaning yet gendered advice and upbringing risks establishing an

unequal and dangerous imbalance in relationships that can go horribly awry.

Why We Need To Talk About Dickpics.

It is important to address the issue of unsolicited explicit images, commonly referred to

as "dickpics," and their impact on women both in public debates and in private

interactions. The non-consensual sharing of such images is a form of sexual harassment

and a manifestation of gender-based violence. It reflects broader societal issues regarding

consent, respect, and the objectification of women.

In the realm of public debate, the sending of unsolicited explicit images can be used as a

tool for intimidation and silencing. Women who are vocal in public forums, particularly

on topics like feminism, politics, or gender equality, often find themselves targeted by this

form of harassment. It's a tactic used to demean and belittle women, attempting to

reduce their public presence to a sexual object rather than a respected voice in the

discussion. This can have a chilling effect on women's participation in public discourse, as

the threat of receiving such images can lead to self-censorship or withdrawal from online

platforms and public spaces.

Privately, the unsolicited sending of explicit images is a violation of personal boundaries

and an act of aggression. It imposes sexuality into a non-consensual context, which can

be particularly disturbing and traumatic. Women on dating platforms or social media

frequently encounter this issue, and it contributes to an environment where their online

presence is constantly subjected to sexualization and disrespect. This behavior reflects a

broader societal problem where some men feel entitled to women's attention and bodies,

without regard for consent or mutual respect.

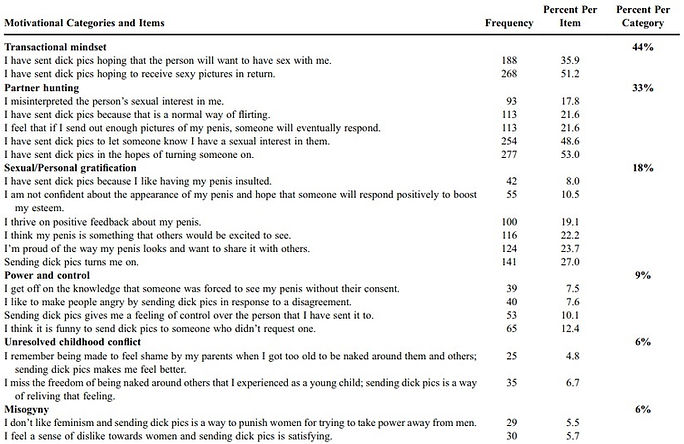

The research article, I’ll Show You Mine so You’ll Show Me Yours: Motivations and

Personality Variables in Photographic Exhibitionism19, posits that there’s numerous

motivations for men in sending such images, as seen in the below table.

The cases in the present analysis suggest a motivation of either ‘Power and control’ and ‘Misogyny’, which both are statistically relevant and serious, as well as targeted uses of such imagery. They do not have the same (still non-excusable) built-in argument of

misunderstanding sexual signals (‘Partner Hunting’ or ‘Transactional Mindset’). As they are part of a social or personal conflict ‘Sexual/Personal Gratification’ seems unlikely as the primary motivator, as well as ‘Unresolved Childhood Conflict’. Thus it stands, that for the present analysis, dickpics are weaponized to target women, and from a digital distance - and potential anonymity, subject women to gendered sexual abuse.

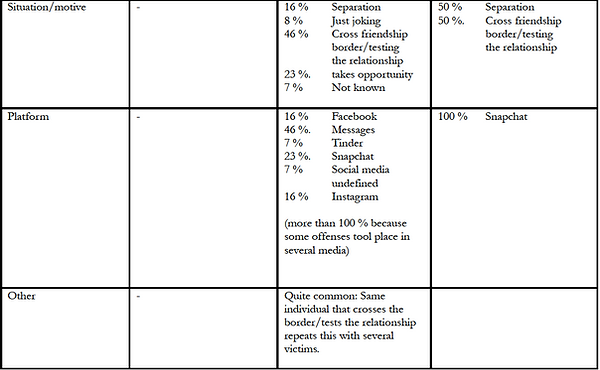

Moreover, several data points in analyzed police cases (particularly Swedish), show that the men who had sent dickpics to others, often did it to “test the friendship”, an argument also made in some Danish examples. The impact of receiving unsolicited explicit images can be profound. It can lead to feelings of violation, disgust, and fear. For some, it can trigger anxiety or exacerbate

existing trauma. The psychological impact of this form of harassment is an area that requires more attention and understanding.

Addressing this issue requires a multifaceted approach. There needs to be a greater emphasis on educating individuals, especially men, about consent and respectful communication. NORDREF is meeting this need by building on the results of this

research in the Game Changer project, where material aimed at young men is being created that identifies harmful behavior while giving examples of more constructive communication. Social media platforms and dating apps need to implement stricter policies and technological solutions to prevent the sharing of unsolicited explicit images. Legal frameworks should also recognize the non-consensual sharing of explicit images as a form of sexual harassment and provide appropriate avenues for recourse.

Furthermore, there is a need for broader cultural shifts. Society must challenge and change the norms and attitudes that underpin such behaviour. This includes dismantling the objectification of women, promoting healthy masculinity, and fostering a culture

where respect and consent are paramount.

In conclusion, the issue of unsolicited explicit images is a serious form of gender-based violence that affects women both publicly and privately. Combating it requires educational, technological, legal, and cultural changes to ensure that women can

participate in public and private spaces without fear of harassment or violation.

Denmark.

Methodology

As proven by digital violations experienced first hand by members of our Board, sexually explicit material can be stolen by hackers who ransack email/social media accounts or

cloud services. Victims do not need to be famous celebrities for this to happen to them.

Sexually explicit material can be - and is increasingly - made by Generative AI technology, as is now the case with twenty girls aged 12-17 in Spain in a high-profile case. Again, not

celebrities. As a result, it's factually incorrect that those close to the victims are the only people who can use sexual material to harass and violate them.]

There are too few respondents confirming the gender of the perpetrator (2, male) or the relationship to them (1 romantic, 1 professional) to note any statistical significance in either direction. A cursory note is made that 100% of the confirmed responses indicate a male as the perpetrator in regards to sharing sexual material without consent, which

follows initial assumptions.

In Denmark the victim-based data set is collected in collaboration with Dansk Kvindesamfunds Krisecentre (National Women’s Organization’s shelters), and Stop Chikane (national organization to combat gendered harassment), via only one local unit. The questionnaires have been shared digitally and filled out on a voluntary basis, with minimal encouragement from staff. The minimal encouragement from staff was agreed as a prerequisite for the collaboration, as neither researchers nor staff wished for the primary concern of the shelters (to provide acute and immediate supportive housing for women in need) to suffer under any potentially perceived necessary reciprocation from the women.

As the research targets to support further developments of perpetrator profiles, initial research questions focused on interviewing and describing these directly. Yet as the abuse is simultaneously veiled in social taboo and societal indifference, it is ironically both a too serious and a not serious enough problem at the same time, for there to exist perpetrator profiles and databases that the researchers could utilize. Yet, the victims and the effects of the abuse and attacks are very real. This, in combination with the fact that perpetrators are less likely to cooperate with research projects such as this for obvious reasons, the researchers therefore focused on victims and their perception of the abuse and the perpetrators.

Court Data

The data from the Danish courts and police are centralized and digitized, yet not freely available to Danish citizens. The Danish Attorney General (Rigsadvokat) has provided overview statistics that have been compiled in the research group. Furthermore, the singular court cases are open to the public, but must be applied for on a per-case basis, with a motivated communication, which has resulted in a most troublesome

data-collection process for the Danish cases. The freely available Danish database for court cases, www.domsdatabasen.dk, is neither exhaustive nor complete, and holds only an unsatisfactory percentage of the full judicial history. As such, the Danish court data is not an exhaustive and complete analysis, yet it still provides valuable insights to the area on a case-by-case basis. In comparison with the Swedish database mentioned later, the Danish sadly does not offer the same comprehensive insights.

Existing Data

In Denmark digital abuse is often treated as a localized problem, often thought to only be relevant in youth circles, or for particularly exposed victim groups (politicians, celebrities etc.). As such, most collective data are focused on not general population studies but niche concerns such as mentioned above. Danish NGO, Digitalt Ansvar (Digital Responsibility), built a generalized data-set in 2020 via public polling company Epinion, which showed that out of 1.000% Danes:

- 5% were experiencing hateful comments or malicious lies regarding their person.

- 6% were experiencing sharing of private information or media (e.g. images).

- 4% were experiencing digital harassment or stalking.

- 6% were experiencing extortion, blackmail or threats.20

Danish Police have noted that in spite of a steady increase in the number of complaints about relevant digital abuse cases, there is still thought to be a very large number of unreported cases. National experts have noted that the increase in complaints does not even necessarily imply an increase in cases, but rather that more victims trust the police to “do something”21 22.

Examples of localized data would be for an example that the Danish National Crime Prevention Council (Det Kriminalpræventive Råd) found that 4% of Danish youth “often” had been shown illegally shared private photos/videos of others (that was known to be illegally obtained), 19% had experienced it “several times”, and for 17% it had happened “once”23. The same study shows that 36% of Danish primary schools have had (at least) one case of image sharing abuse within the last year, but also notes that most cases are not found

out about by teachers, as pupils often won’t share such information.

This researcher with country-specific knowledge notes that as digital endeavours are often thought to be predominantly for and by the youth, so is digital abuse and crimes thought to be a problem only pertaining to the same demographic.

One national survey (National Victum Survey, Ministry of Justice, 2022) finds, that one of the reasons for under-reporting of digital sexualized abuse and harassment (coded as “Other sexual crimes than rape”) is a fear that the police will not prosecute properly, a feeling of personal shame, or the relation to the perpetrator.24

Another national survey (National Victum Survey key figures 2005-2022, Ministry of Justice, 2022) finds that 0,4% of a representative population sample have received digital threats or harassment, 0,4% have had their personal information digitally shared/misused, and 1,3% have been subjected to “other sexualized crimes than rape” (not necessarily digitally).25

As such, Danish public data suggests an image of a problem that is garnering concrete and serious attention both in media and politically, but often falls between two chairs: It is either grouped as a digital crime alongside digital theft, online fraud etc., or as a “sex crime” in the same category as indescent exposure, rape etc., or even as an expression of youth culture. Too seldom is it treated as the ugly result appearing in the juxtaposition of all of the above; a gender-focused digitally committed crime and/or harassment with the aim to harass, terrorize or threaten both the victim and their comparative demographic group.

Data Collected

Victim Questionnaires

The data collection from victim organizations in Denmark has been tentative and provided fewer results than hoped and expected. As the system of women’s shelters and support systems is already extremely taxed, the research groups’ understanding is that neither staff nor victims have had the emotional bandwidth to support the research project, and fill out the questionnaire. The amount of answers is in no way a reflection on a lack of severity or seriousness of the issue in Denmark, rather, it is the opposite. Underway in the process, the women’s shelters were given a tablet by the research group, with the explicit purpose of having the questionnaire in a readily and available format at the shelter. This initiative did not provide any increase in responses, which stands at 31.

The research group proposes to include the answers as statistically relevant, but that their conclusion must be aligned with, and seen in the context of, bigger national data-sets from comparative countries in the analysis, and should not be concluded upon alone. 30 respondents have answered in Danish, and 1 in English.

All of the respondents’ answers accounted for here, have consented to have their (anonymous) data used for the present research purpose. 29 of the respondents are women, and 2 are men.

The majority are in their 20’s (21, 68%), and the rest are teenagers (3, 9,5%), in their 30’s (3, 9,5%) or older (4, 13%).

Threats

16 (51,5%) respondents have been threatened with rape or grevious bodily harm, either to themself or someone dear to them. Out of those responding positively, almost all of the threats had been made by a man (86%).

The majority of the perpetrators were under the age of 30 (8, 57%), with fewer (5, 36%) being older. The rest of the victims did not know the age of the perpetrator. A distinct outlier was that 2 respondents had been harassed by perpetrators younger than 18. As the data is collected from Danish Women’s Shelters, where users have to be of age (18 in Denmark), this implies a decoupling of victim/perpetrator relationship, that is evident in most other responses to the questionnaire.

Relationships between victim and perpetrator were equally shared among romantic (4, 29%), friendly (4, 29%) and none/stranger (4, 29%), whereas a few (2, 13%) had been committed by family members.

Sexual material (received)

Fourteen (45%) respondents have been sent sexual material (either graphical or textual) that they did not want or consent to receive. A slight majority (5, 35%) do not know if it is the same perpetrator as for other categories, and an equal number of respondents say that it was the same perpetrator (4, 28,5%), or that it was not (4, 28,5%) respectively. None of the victims report that a woman sent sexual material to them, but there is an equal share of men as perpetrators, and non-confirmed perpetrators.

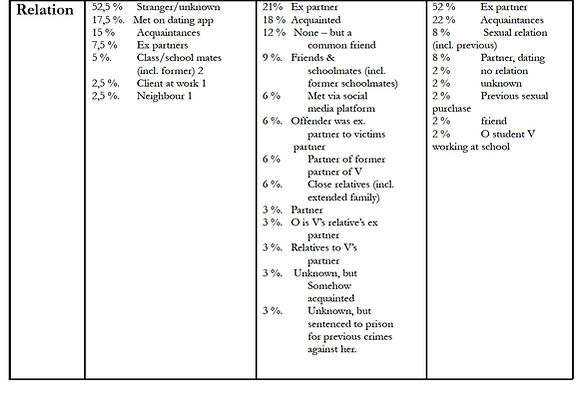

An interesting figure is that none of the recipients of sexual material had a relationship to the perpetrator. All who can confirm their relationship (5) categorize it as non-existent. As we shall further discuss later, this posits the analysis that forwarded sexualized material is more often than not a harassment tactic used to target victims outside of the perpetrators immediate social circle. -Though noting that it can very well be motivated or even organized by someone within the victims social circle. The same tendency is clearly seen in the Icelandic data.

The preliminary conclusion that unsolicited “dickpics” are sent by strangers, supports the notion that a non-negligible number of men send such pictures in order to impose feelings of distress, unease and disgust with their recipients. Dickpics as such are not just attempts at flirtation gone (very!) wrong, but also a weaponization of some men’s own sexuality26.

Sexual material (shared w/o consent)

13 (42%) respondents have had personal sexual imagery or media shared with others without the respondent’s consent, or have been threatened with it. More than half of these (7, 54%) can confirm that it is the same perpetrator as in other categories, and whilst fewer (4, 31%) do not know if it is, only 2 (15%) can deny that it is.

These numbers provide an understanding of the fact that the sharing of sexual material is a crime and harassment strategy often done by those close to the victim, as these would be the ones having easiest access to the material in the first place. Outliers to this theory would be celebrities, where the general public assumes a parasocial relationship to the celebrity and thus feel entitled to imagery should hackers or people in actual social vicinity of them share such imagery, or to cases that garner media attention that the victim, or at least their cases, because somewhat (in)famous for a newscycle or two.

Hate speech &

harassment.

19 (63,3%) of the respondents have received abuse and harassing language either in direct

messages (DM’s), social media communication, email or the likes. Half confirm that the

perpetrator is the same as in other categories. We make a note of the fact that women are

often targeted personally on gendered aspects of their identity or appearance (sexuality,

“sexiness”, makeup, clothing etc.) more so than men27, and therefore these numbers can

either be part of a broad stalking- and harassment-picture, or simply a sad witness to the

everyday life of a woman with a digital presence.

These findings are supported by existing literature, emphasizing that women historically

have been evaluated as per their physical appearance, and men conversely on their

behavior/performance.28

A third (3, 33%) of the confirmed responses report that a woman was doing the

harassment, whereas a majority (5, 55,6%) report a man, with the rest not knowing for

sure. The ages of the perpetrators vary but a slight majority (5, 55,6%) are under the age

of 25. The predominant relation between victim and perpetrator seems to be friendly (4,

44%), and only 2 (22%) report strangers as perpetrators. The latter fact speaks to the

theory posited above, that hate speech and harassment is simply something that happens

to most women online.

Police

reporting.

20 (65%) of the respondents did not report the abuse to any authorities, yet 5 (16%)

reported it to the police, 1 (3%) to the online platform used in the abuse, and 4 (13%) to

both police and platform. The large proportion of respondents that say they have been

targeted with digital abuse and/or harassment yet who did not report it, is in no way an

indication of the attacks not having a large effect on the victims. Rather it is indicative of

victims being afraid that the police will not be able to handle the case, either by technical

ineptitude, gendered biases internally in the police, or other reasons. Some victims also

fear further repercussions from the perpetrator if they choose to report them. These

points shall be further elaborated in the present paper.

Five (50%) of the reported cases have not reached their conclusion, as of the time of the victims’ response, yet none of the respondents say that the case outcome was that they found fitting or just. A single respondent does not know the outcome of the case.

Respondents’ comments

Lastly in the questionnaires, respondents had the option to include details or elaborations to their answers. A few are included in the present analysis, yet all are read and a part of the research team’s understanding of this problem, as it persists on a social scale. (Responses here have been anonymized and re-written to protect respondents)

“The police are too slow to do their job. I reported this in [more than six months prior to the questionnaire], and they have neither called nor written. It was like they didn’t care about what I told them. Maybe I am not the only one with such an experience with the police. He just sent the pictures to my youngest daughter. The police still haven’t reacted.”

“My partner suddenly took out their phone during sex in a somewhat public place, and even though I didn’t want it, I couldn’t tell them no. We broke up not long thereafter, and I asked him to delete all such stuff. He called me two years later while drunk, and told me that he still had the material, and although he said he hadn’t shown it to anyone, it made me feel unsafe. Maybe he has more videos than I know of.”

“My then boyfriend was the one harassing me. He pretended to be someone else.”

“A buyer whom I didn’t know got my personal information off of Facebook Marketplace, as we were buying/selling, and started using it to harass me.”

Preliminary

Profile of

Danish

Perpetrators.

These findings suggest a cursory national profile of perpetrators of the analyzed crimes

as falling into one of two categories, both of which are predominantly male and in or

around their 20’s.

One suggested profile of the perpetrator is that of the malicious stranger, who does not

have a direct or concrete relationship to his victim, but either engages via social media

platforms, or pure coincidence. His targeting will typically be one-of, and not transgress

abuse categories, and as such suggest a higher propensity for doing a certain thing for his

own gratitude, rather than to obtain a concrete goal. The method of abuse or harassment

is the goal of it in itself, so to speak.

The alternative profile is the relational abuser, who does have a direct (at least perceived)

relationship with the victim. This will most likely be or have been romantic in nature, but

could subsequently be professional or even platonic. Victims who indicated a relationship

to their abuser, also reported that the abuse and harassment spanned multiple categories,

and as such can be understood as tools employed in order to reach a goal, rather than

being the goal in itself. This overarching goal can either be re-kindling or reigniting a

relationship, silencing certain behavior or opinions, or to enact a form of revenge on the

victim.

Although both categories of perpetrators would be greatly mitigated by an increase in

both social awareness of gender-based violence, and the technology facilitating it, solving

the former “only” requires humans to change their actions, whereas the latter would need

for digital media platforms to change their design and legal frameworks. -Which of the

two can be achieved the fastest is sadly outside the scope of the present analysis.

We note however, that as digital platforms and GBV alike only serve a (“)higher(“) goal -

to target, abuse and deplatform women, should some technology change, perpetrators

would be highly motivated to find other platforms and digital tools that would support

their abuse. Especially perpetrators of the latter category (relational abuser) can thus only be stopped

by:

- Their own volition.

Which in cases of stalking, harassment and targeted GBV-statistics rarely

happens.

- By the police.

Which as explained above by victims, can feel like a very distant possibility.

- By obtaining their goal.

As the goal very often can be hurting the victim, this is not an advisable

strategy.

Judicial Analysis

In the analyzed timeframe for the Danish judicial data (2018-2022 both included)29 there

has been an increase in both reports and convictions for the three sections of the penal

code this report pertains to, §§ 232, 264d and 266 respectively. These are covering the

most relevant examples of digital sexual violence, to this study. Namely:

§232

Anyone who, through indecent conduct, violates modesty, is punished with a fine or imprisonment up to 2 years or, if the act is committed against a child under 15 years, with a fine or imprisonment up to 4 years.

§264d

With a fine or imprisonment up to 6 months, a person is punished who unlawfully discloses messages or images concerning another person's private affairs or otherwise images of the person in question under circumstances that can evidently be expected to be kept away from the wider public. The provision also applies where the message or image pertains to a deceased person.

Subsection 2. If there are particularly aggravating circumstances, considering the nature and extent of the information or disclosure, or the number of affected individuals, the penalty can increase to imprisonment up to 3 years.

§266

Anyone who, in a manner likely to induce serious fear for one's own or another's life, health, or welfare, threatens to commit a criminal act, is punished with a fine or imprisonment up to 2 years.

Reports – Total

Convictions – Total

The comparatively high conviction rate of gendered violence bears evidence that once

reported these crimes are taken seriously, and to a somewhat satisfactory degree lead to a

conviction in Denmark. As evidenced by the questionnaires this can be a challenge

though. Anecdotal and case-based narratives from Danish press shows that a large

number of especially women feel turned away by local police, when initially wanting to

report gendered crimes (both the paragraphs mentioned in the present analysis, and rape,

domestic violence and more) 30 31 32. A large number of victims cite expected “victim

blaming” as the reason for giving up on any initial reporting, thus omitting themselves

from the emotional labor and distress of convincing someone of their victimhood.

The umbrella effect.

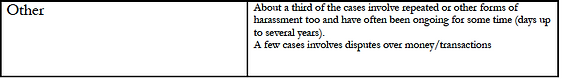

Overall the data suggest a steady increase in reports and percentile convictions. The year 2019 seems to be an outlier in quantitative metrics, as there is both a sharp increase 2018-2019, and a less but still significant decrease 2019-2020, particularly §264d. One possible solution for this outlier-effect of 2019 could be that given Denmark’s relatively small size, one single case could offset any linear expectancies of the statistics.

In 2018 one of the biggest cases of digital sexual abuse aired in Denmark, and the convictions carried well into 2019 (and 2020 subsequently). “The Umbrella Case33” was a year-long case and trial wherein two victims (1 male and 1 female, both aged 15) in 2015 had videos of a sexual encounter at a party shared without their consent. Danish Police

cooperated with Europol, Facebook (now Meta) and other parties to unravel all of the pathways the video had been shared through. In the end, the police ended up charging more than 1.000 young people in Denmark per §264d, and obtained convictions in most cases. Comparative to the statistics above, such singular but monumental cases can risk skewing data sets, as is expected to be the case presently.

Danish Police Data

The police data requested was requested from Anklagemyndigheden (Public Attorney),

who specified the requested number of case files, to further be requested in effect from

regional police offices. Some cases were available via the Danish Court Digitization

Project (Domsdatabasen.dk), and were collected per responding case numbers from the

initial overview from Anklagemyndigheden.

Sadly, only a few of Denmark’s regional police were forthcoming in regards to requested

case files. An ongoing conversation to collect and analyze more case files is, as per the

day of publication, still underway, and will be attached separately.

Some of the declines were based on protection of those involved in the cases - both

perpetrators and victims. This in spite of a written testimony that no personal

information, personally referring information or the like, would be shared or publicized.

As is, the case files have informed the rest of the analysis and provide unique perspectives

as to the nature, motivation and possible prevention of any such future abuse and crime.

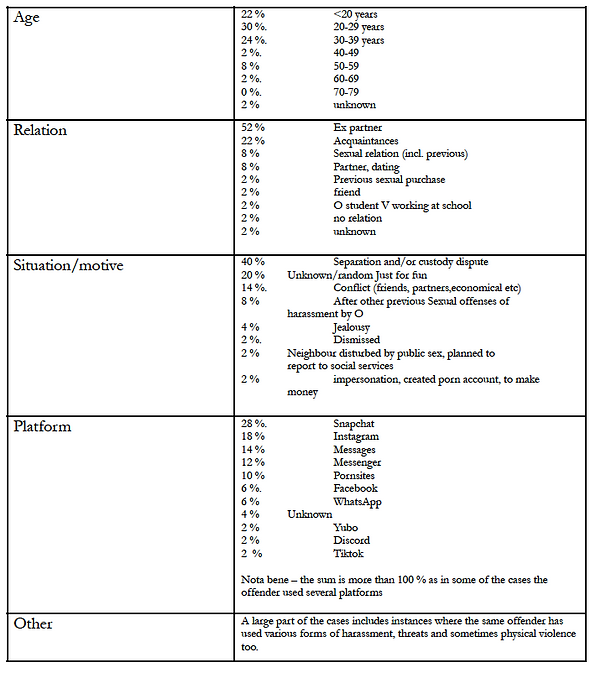

The preliminarily attained data shows:

- More than 90% male perpetrators, between the ages of 16 and 54.

- Harassment done via many different platforms, although Snapchat is prevalent in

regards to both threats and sexual harassment.

- The relationship between perpetrator and victim is more often than not romantic,

or has been. Both fully consummated relationships, past and present, and some

with only one party being interested in pursuing it, where the motivation would

then often be vengeance.

- Most cases with a guilty conviction have a relatively mild sentencing, mostly

suspended sentencing.

- Most cases are in the system for an extremely long time, several over two years.

Supplementary perspectives

The research group has prioritized access to former Danish surveys and analysis on

comparative topics, namely The Angry Internet (Mogensen & Rand, Center for Digital

Youth Care, 2020), and data from Vi Kommer og Dræber Dig (Mogensen, on behalf of

LAUD TV, 2022).

The Angry Internet

The Angry Internet sought to identify and understand the motivations, extent and

ideology of online misogyny from international digital forums, but specific to Nordic

users. The results and the full study was published by Center for Digital Youth Care in

2020, and is freely available online34.

In order to assess the scope of the issue of online misogyny in the Nordic countries, data

was gathered both qualitatively and quantitatively through multiple methods: field

observations, interviews with experts, quantitative extent analysis (Twitter, 4Chan &

(sub)Reddits), focus groups, and expert advisory groups.

One of the data sets from the study identifies the prevalence and nature of some of the

misogynistic phrases used on the forums. The authors note that the users employ such

language both from a misogynistic perspective - to belittle and vilify women, but also to

“prove allegiance” to the in-group.

Broadly the data suggests that the by far most used category of derogatory terminology

about women is sexualized content. Phrases and words depicting women (both

individuals and as a gender) as overly promiscuous (which internally to such forums is

understood as being very bad), or not promiscuous enough (which, ironically is

understood as equally bad) are used more than any other category.

Generally there is a mindset of “punishing” or shaming women for their sexuality (or lack

thereof), and attaining and subsequent sharing of their intimate media content, is an oft

discussed and much lauded strategy for such. Either to reaffirm the “fact” that “women are

too slutty, and they shouldn’t be!” or to enforce a perspective of “she isn’t acting slutty enough, we

deserve her sluttiness!”.

In the analyzed data, women are on a whole objectified and treated as something the forum users have a right to, or should be “awarded” if societal duties (education, job, values) are satisfactory. As such, the womens’ sexuality becomes a currency which the users can appraise and manipulate by (trying to) control how often it is used. This data lends credence to the earlier suggested perpetrator profile of the malicious stranger, as the forum users would very seldomly know the women in question, but rather randomly have seen their social media profiles, or come in contact with their identity through different means. Some would also target celebrities in a parasocial misunderstanding of having a “right” to their sexuality.

A counter narrative

In opposition to the above proposed theory of digitally enabled malicious strangers, would be one of perpetrators already with an established relationship, or means of communication, with their victim then choosing to employ digital means to harass said victim. As the gathered evidence in the present report suggests, a substantial amount of the analyzed verdicts support this profile, as the partners or romantically interested individuals, make up the majority of the perpetrators across all three countries. -Even if one excludes data from shelters, where victims exclusively have an established relationship with at least one of their perpetrators, it stands to reason that digitalization of harassment is at least sometimes a conscious strategy, and not only an opportunistic one. As no substantial data from perpetrators on their motivations exists, we can only posit guesses as to the reason for digitizing harassment as suggested above. As an overwhelming majority of the responses of the questionnaire for the present projects indicate, digital harassment is seldom met with satisfactory response from neither

platforms nor local police. To a large degree, it is therefore a crime that many - both victims and perpetrators - think to be done without consequence for the perpetrator. Therefore, it is not unreasonable albeit impossible to prove, to think, that some perpetrators choose digital means of harassment to inflict harm on their victim, as they risk very few repercussions this way - compared to physical harassment and violence. The conviction rates included earlier are higher in digital cases than in physical cases, which posits that cases that do go to trial are duly tried. The victims’ dissatisfaction with the case handling thus suggests that many cases are not investigated properly, and therefore never see trial. Only those that come with very strong evidence, or have a “lucky” pick of investigator, do.

Vi kommer og dræber dig!

In the TV-series, Vi kommer og dræber dig! (We’re going to kill you!), several Danish women (politicians, cultural figures etc.), shared their story of being targeted with gendered abuse. Most of the content targeting the women was sexualized in nature, and although the series focused on finding the specific perpetrators, both a qualitative and a quantitative approach to different (smaller) sets of data was analyzed by the host and other experts. In one instance, a very broad selection of Danish politicians and media personalities was asked to share any imagery, texts or the likes they had received, because of their public persona. A large number of women (no men) had received images of strangers’ genitalia (exclusively from men). The text accompanying these images was analyzed, and provided a few interesting points:

None of the image senders knew their victims; all of the text was either greetings (“Hello. What do you think of this one?”), or sexual questions (“I have this much penis. Do you want to have sex?” or “Is this enough penis for you to want to have sex with me?”), suggesting that those sending unsolicited dick-pics seldom know their victim. -Most likely, one could note, because such image-based communication would instantly end any existing relation. Another subset of data analyzed for ‘Vi kommer og dræber dig!’, was texts (social media, emails, notes etc.) the same general group of recipients as above had received, though noting that a select subset hereof received more and more specific than others. These texts included threats to the recipients themselves, but also their families, social circles, organizations etc. The initial analysis found that most of the texts were connected and were all but proven to stem from the same (group of) perpetrators via linguistic and stylistic analysis.

These threats were also accompanied by derogatory and gendered abusive terminology and phrasings, which also lend evidence to supporting a profile of the perpetrator(s). Namely, it was evident that the focal points included the victims’:

- Perceived “sexiness”

- Sexuality (be it either too overt, too distant (if i.e. homosexual)

- Age (either too old to “deserve” spotlight, or too young to be taken serious)

- Education level (either too high “to understand the real world”, or too low to understand the “relevant” theories)

- Race (if the women were anything but 100% caucasian this was a derogatory point)

This subset of the data and perpetrators are much more aligned with the (parasocial subset of the) relational abuser profile, mentioned earlier. As there is not a relation from the victim to the perpetrator, yet a perceived or imagined one from the perpetrator to the victim, the parasocial aspect is important to include. This is not a case of vindictive abuse from a spurned lover, although it might feel as such to the perpetrator. During the initial analysis for ‘Vi kommer og dræber dig’, the working theory was that the motivation for the abuse primarily was political, as the victims to varying degrees were engaged in egalitarian work or activism in Denmark, and that the hate speech targeting them more often than not had extremely gendered or referential connotations. It is proven several times over, that ‘gender equality’ or ‘racial equality’ are two of the most “explosive” topics for women and minorities to work in, with regards to receiving hate speech, abuse or being targeted through other malicious digital activity35.

Notes

It should be of no surprise to any interested parties of this research, that digital developments in general move faster than bureaucracy. Particularly in the later years where social media platforms have spearheaded mind-boggling technical leaps and bounds, whereas the judicial system in Denmark more or less have stayed the same. Isolated this is not a dangerous or harmful asynchronicity, yet it underlines a fundamental difficulty in segmenting and analyzing data from the Danish system: Often, one simply does not know what a given penal code is being used for.

Gendered Violence and Harassment is Not Taken Seriously

In Denmark, several cases and situations highlight issues related to gendered harassment

not being taken seriously, reflecting deeper societal challenges in addressing gender

equality and violence.

The Nordic Paradox: Denmark, despite its high ranking in gender equality, faces

significant issues with gender violence. Danish women have reported the highest levels of

physical, sexual, and psychological violence in the EU. In 2014, the EU’s Fundamental

Rights Agency revealed that 52% of Danish women experienced physical and/or sexual

violence since the age of 15, the highest in the EU. The Danish media initially ignored

and even rejected these findings, attempting to close the debate on the issue.36

Challenges in the Military: In the Danish army, there have been issues of harassment

faced by women. The consensus culture in Danish society, which often justifies actions

deemed "well-intentioned," leads to a tolerance of sexual harassment in some cases. This

reflects a broader issue where the evolution of customs and attitudes towards gender

equality is lagging behind legal advancements.37

Legal and Governmental Responses: Efforts have been made to address these issues,

including the establishment of a Gender Equality Office in the Faroe Islands in 2019 and

amendments to the penal code regarding sexual assault. Denmark has also passed a new

rape law based on the criterion of consent. However, challenges remain in ensuring

employer responsibility in cases of sexual harassment and in effectively addressing online

harassment against women. 38

#MeToo Movement's Influence: The #MeToo movement has been significant in

Denmark, with widespread debate since 2017 - and the reinvigoration in 2020. The

Danish Institute for Human Rights has urged the government to take more

comprehensive measures to hold employers accountable for sexual harassment, not only

by executives but also by colleagues and customers.39

Domestic Violence is prevalent in Denmark: A research project in forensic medicine

from 2019, shows that more than 50% of femicides in Denmark are committed by the

partner. Over 25 years, 300 of 536 femicides were committed by the respective partners.

Comparatively, only 79 out of a total 881 men were killed by their respective partners.

(Most prevalent male relation was gangs).40 Data from the Danish Ministry of Justice

show that almost 21% of all killings in Denmark 2017-2021, are partner killings, almost

exclusively with female victims. In a majority of the cases, the murder is prefaced by

physical violence, different forms of harassment or stalking41. This further establishes the

present report as a potentially preventive tool for future work.

National sources:

Iceland

Icelandic Perspective on Research Questions.

Existing data

The National Commissioner for the Icelandic Police annually commissions an annual

survey measuring the prevalence of violence in Icelandic society and trust to the police.

From the survey exploring the state of play in 2021, just under 1% of the population had

been victim of image based sexual abuse, and 2,1% had been threatened to have their

intimate images disclosed without consent. The majority of the victims were women in

the age of 18 – 35. When asked about their relationship to the perpetrator, nearly 40% of

the cases involved former spouse, 37,5% a person the victim had only had sexually

intimate relations with online, 30% had had sexual relations with the victim but did not

have a friendship or another form of social connection with the perpetrator and in 22%

of the cases the perpetrator was friends with the victim. Only 15% of the cases involved a

perpetrator that was a stranger or unknown to the victim. The violation had much or

severe impact on 74% of the victims, compared to 59% of those threatened with image

based sexual abuse.42

Data collected

Victim Reports

Interviewing perpetrators comes with significant restraints. To find interviewees there

would have had to have been an access point. During the time of the project

development the only program providing support and rehabilitation for perpetrators of

sexual abuse was available for young offenders as a part of the Child Protection Services.

The ethical and practical challenges involved in accessing this group were deemed too

high for this project. Further, the dataset would have been impacted by the fact that the

three comparative countries do not have a uniform rehabilitation program for the young

offenders and there would be a risk of contamination. At the time, there were no

rehabilitation programs available for adult perpetrators in Iceland, although this has been

made available since 2022.43

The data set from victims is collected in collaboration with three domestic partners:

Stígamót,44 the leading support centre for victims of sexual abuse in Iceland, the womens

shelter Kvennaathvarfið45 and the family justice center Bjarkarhlíð.46 All partners have a

strong profile as a place for victims of abuse to find support and advice. Even if the

Bjarkarhlíð family justice center has a police officer on site, victims do not have to press

charges and can seek support and advice regarding their cases without any pressure to

lodge a formal complaint or press criminal charges.

The three organizations have different mandates and target audiences while all are

focused on supporting victims of sexual and gender-based abuse. By partnering with all

three organizations, the data collection should mirror victims that have different

pathways into the support system available to them, and create a dataset that is

measurable against the data from the formal criminal justice system.

The information from victims was gathered through questionnaires presented by the staff

of the partners as a form of their intake procedure. The questionnaires were distributed

to the partners on paper by the researcher, and were also made available online through

Google forms. Due to the COVID19 pandemic, particularly the surge related to the

Omicron variant, the domestic partners of Stígamót, Kvennaathvarfið and Bjarkarhlíð

paused their in-person services and offered services via telephone and internet only for a

few months in late 2021 to early 2022. This caused a delay, so the data collection that was

supposed to start on January 1st 2022 started at the end of the month instead. To make

up for it, the data collection was extended through January 2023 instead, ensuring a 12

month collection period as planned. The questions in the questionnaire described the

issues pertaining to the relevant legal provisions without a direct mention of the Penal

Code.

The uptake of responses started slowly and roughly half way through the data collection

period, in September 2022, the partners were provided with tablets in the hope that filling

out a digital questionnaire would be a more attractive and accessible way for clients to

partake in the research than filling out a paper form. Also, it solved privacy and safety

issues, because creating a protocol around the filing and storage of filled-out paper

questionnaires had proven to be a challenge. Furthermore, a presentation was given to

the staff of all three shelters, educating them on gendered forms of digital abuse and how

it belongs to the continuum of gender-based violence. Following this, the uptake of the

questionnaire improved significantly.

In total there were 262 answers provided. In addition, four forms were opened but not

filled out. The respondents age was from 17 - 70 and the overwhelming majority were

women. The largest number of responses came through Stígamót, Center for Survivors

of Sexual Violence, 112 in total. Both Stígamót and Bjarkarhlíð offer their services to all

genders, while Kvennaathvarfið is only available to women.

Totals

The total number of respondents was 266, with 246 women, 12 men, and 4 non-binary.

The age of respondents varying from 17 to 70, with a relevant declining prevalence

peaking around 20 years of age.

Totals

More than half of the Icelandic respondents have received threats to their own health,

those closest to them, or their belongings:

Out of the 138 positive responses, 116 indicate that a man threatened them, 13 by a

woman and 1 by a non-binary, whereas the rest (8) do not know.

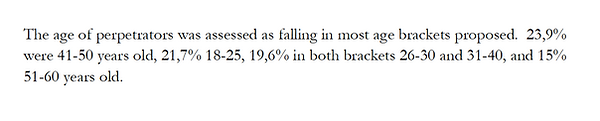

The most prevalent age group of perpetrators are the 18-25 year olds (36), followed by

31-40 and 41-50 (both 23), and 26-30 (22), whereas the 51-60 year olds only account for

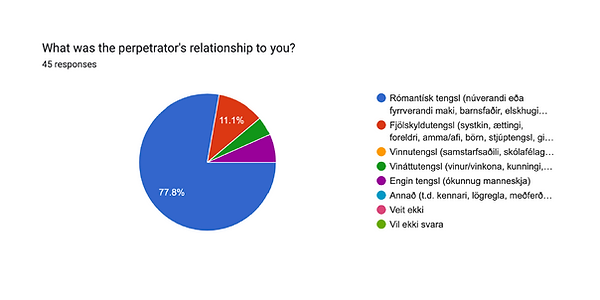

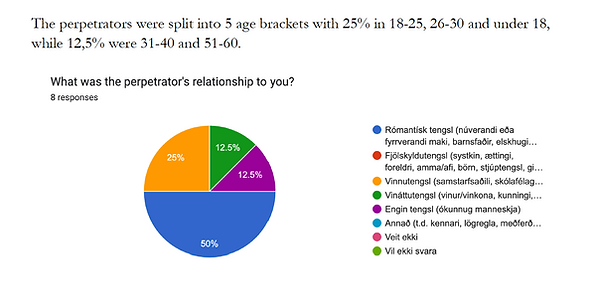

relatively few of the perpetrators (14).